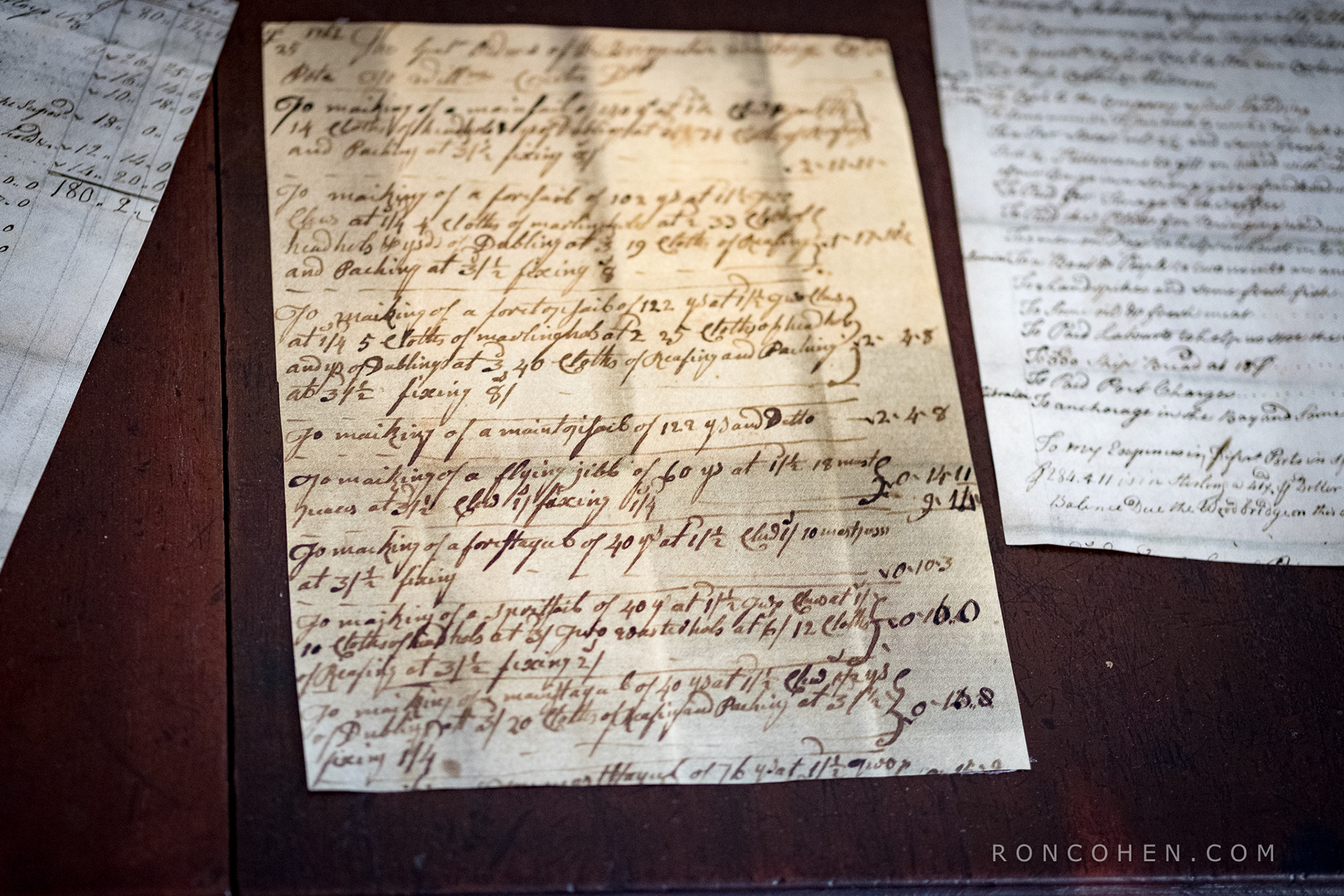

Jeremiah Lee was one of the wealthiest men in the colonies at the time of the American Revolution. He made his fortune not on banking, railroads or oil—these came much later. His wealth was based on the humble codfish, caught in great numbers in the North Atlantic, dried, salted and shipped in wooden barrels to ports up and down the American coast, and across the Atlantic to England, Spain, Portugal and the wine islands.

Lee's secret of success? Today, we’d say he was "vertically integrated." He owned his own fleet of fishing and cargo vessels, allowing him to cut out the traditional middlemen. The fleet’s home port was, of course, the town of Marblehead, Massachusetts, which I covered in an earlier post.

Lee was deeply involved in covert preparations for the revolution. He smuggled arms and supplies from France and Spain for the rebel militias. He died relatively young, at the age of 54, shortly after the revolution began, as a direct result of his clandestine activities.

Because his role was covert, and he died young, he never received the recognition that was his due. You can learn more about this little-known patriot, a key player in the American Revolution, from this concise page, or this more detailed page on the Marblehead Historical Society website.

Lee built his Georgian-styled mansion in 1766-68. It was one of the most opulent houses in the colonies at the time. Sadly, he and his family lived there only seven years before his tragic, early demise.

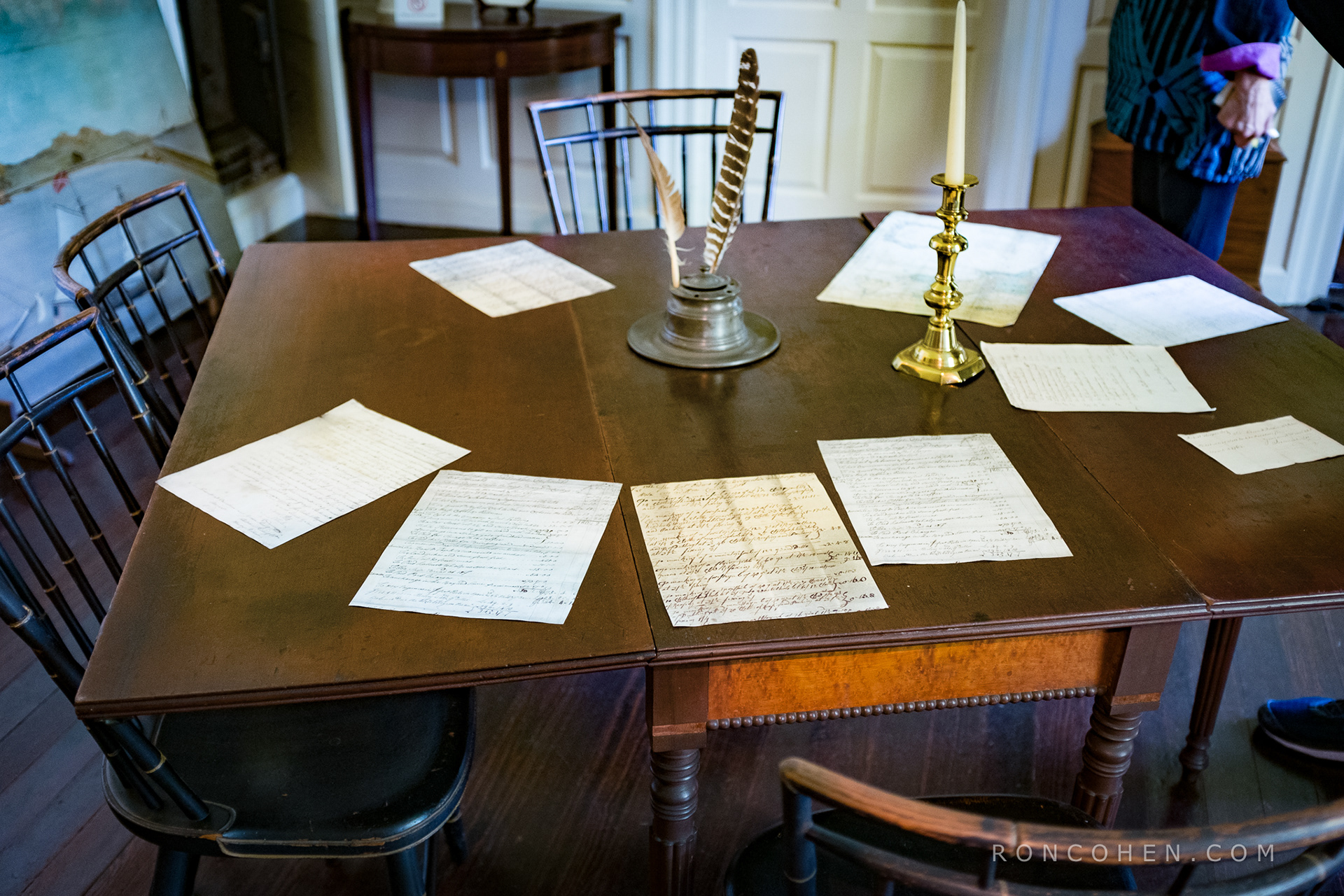

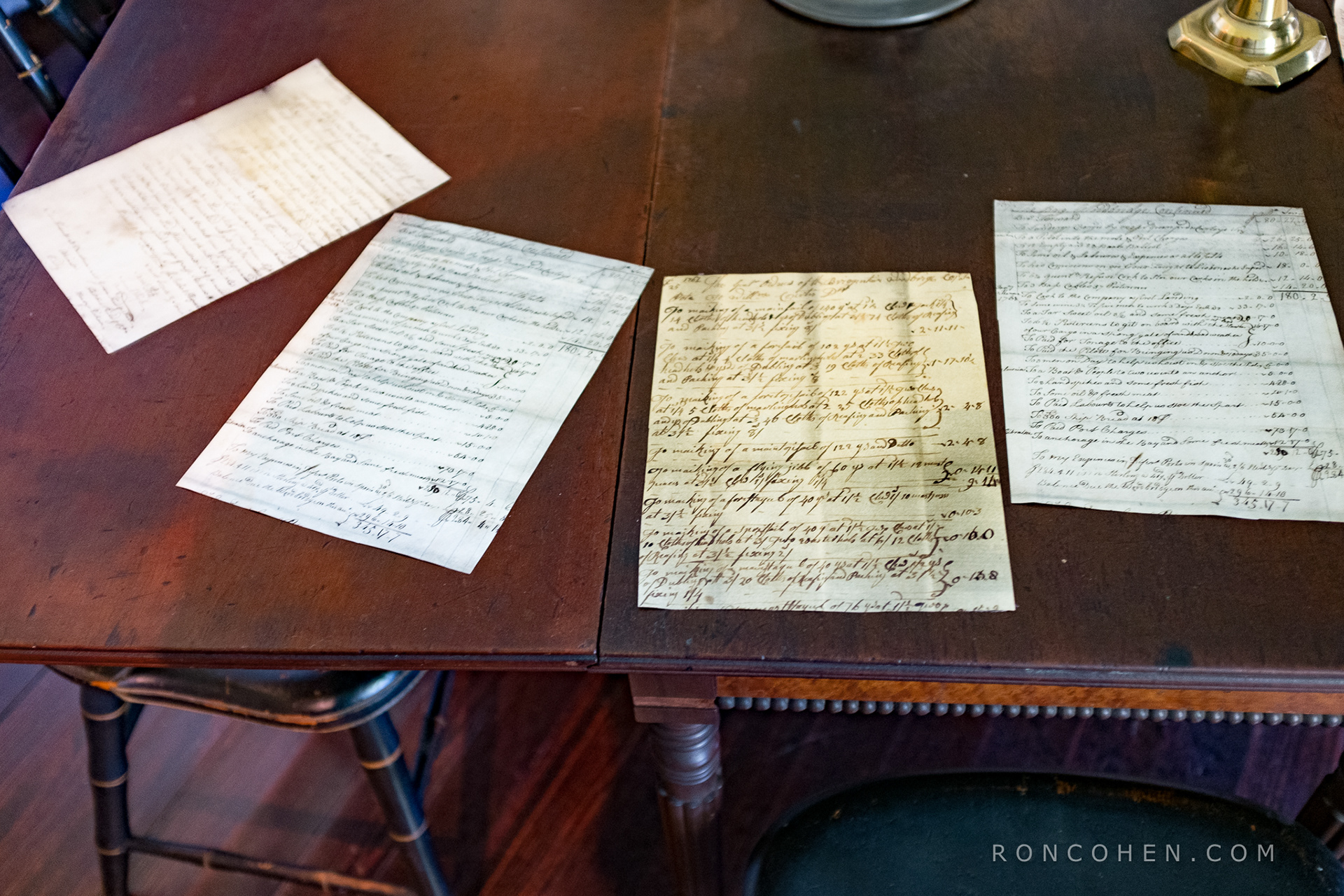

The few photos, below, hardly do justice to this grand, well-preserved house. The rooms are large, high-ceilinged, but dimly lit. Happily, during my visit, shafts of sunlight illuminated many of the furnishings, allowing me to snap them as I walked along with the guided tour.

Most of the fine furnishings were imported from England or France. Heating and cooking depended entirely on fireplaces. The kitchen fireplace featured a gravity-powered, rotating spit. Lee’s own desk can be seen in the fourth photo from the end. The next-to-last photo shows some reproductions of colonial glassware. The last photo is of the house grounds.

Click any image to open slide show. Use keyboard arrows, or swipe, to move through slides: